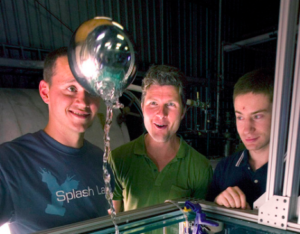

Over the past month the Splash Lab has been featured in the Salt Lake Tribune and The Daily Universe!

The Daily Universe article pretty much sums up what we do here at the Splash Lab.

The Salt Lake Tribune article highlights a few of the things going on in our lab and tells a little about what the Splash Lab does. Here is a an email I sent to Maffly in response to one of his questions as a follow up conversation a few days before it was published. I think it is fascinating to see how these things happen, don’t you?[/fusion_text][/one_half]

—————————-

Subject: Trivial?

Brian,

I don’t know if you got tied up but I wanted to send you some of my thoughts as I was walking around with a student. We are moving the big water tank you saw to another building (with high ceilings) because the vibrations from our power plant are making it difficult to get the water to be perfectly still. I think that this small detail is really important in our findings, and it’s the kind of thing that makes the job non-trivial. It isn’t obvious that we need to have even the smallest vibrations removed so that the impact splash can be properly measured (if there is a wave in the tank the splash is non-axisymmetric, which could influence the trajectory angle!). More importantly the vibrations move the slender body objects enough that they land with an angle to the surface, which has a huge bearing on their trajectory, but we want to set the angle, not allow the ambient vibrations to do it for us.

Ok so here are my more overarching thoughts on how what we do is non-trivial.

What makes my research non-trivial?

This is a hard question it is sort of like asking a chemist “what part of mixing these thousands of compounds is non-trivial?”

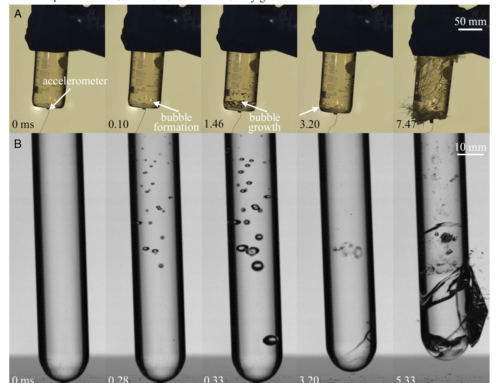

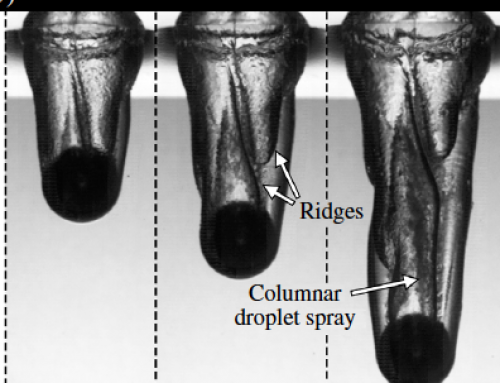

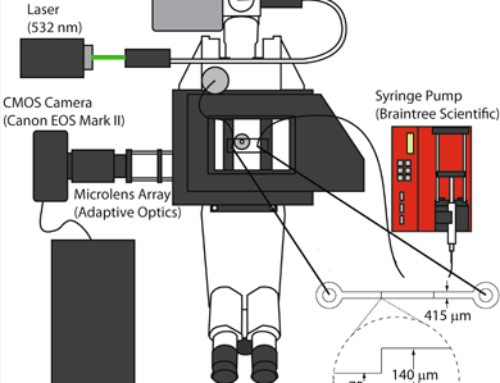

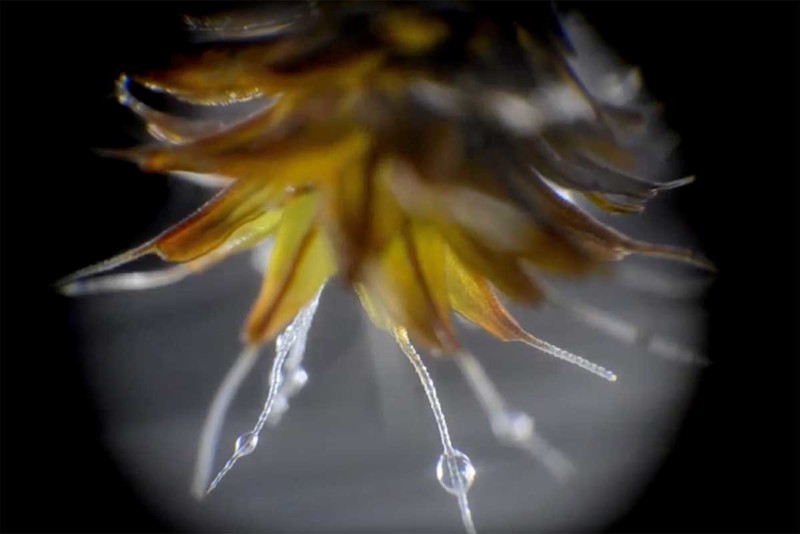

I’d say that any time a researcher does something over and over again there is typically a purpose because by and large humans are lazy. So when a chemist or someone from my lab does an experiment over and over again, there is a reason. For us it is often a way to determine the error or figure out why each time the object behaves slightly differently. We take some seemingly ordinary things and some not so ordinary things and evaluate their behavior very carefully. We measure them with all kinds of instruments and cameras. This part of the work is already very difficult because everything has to be timed just right. Then we take the mounds of data (last year alone it was 1 terabyte, this amounts to over a million images) and we unravel what we saw in a way that tells a story so that other researchers can understand what we write in the journals we publish in. The unraveling is not easy, we read and study as much as we can about imaging techniques and measurement methods to unravel the story, and we write code, lots and lots of code to measure as much as we can from the images and instruments. But, we don’t stop there, we also try to tell the story in a compelling way that keeps the non-scientist and children interested so that we can have some impact on them and their future. If you are looking for trivial, think of the papers I have to fill out to visit a naval base, or report to government agencies that fund us (NSF or ONR). In my mind non-trivial items are the sorts of things that you can get a kick out of, and taking, analyzing and discovering new things about the world around us is the kind of thing I get a kick out of. How about you?

Tadd